Testing registerProtocolHandler and the web+ scheme prefix

30 Jan 2012Note: jump straight to the test page for navigator.registerProtocolHandler and web+ if you'd rather...

A URI (Uniform Resource Identifier) is easily the most recognizable protocol element of the Web. A URL (Uniform Resource Locator) is a form of URI which includes an access mechanism (e.g. a network location). The terms are often used interchangeably, and to add to the terminology, these protocol elements may also be IRIs (Internationalized Resource Identifiers), which can be thought of as a fork of URI that may include characters outside of the US-ASCII character set. So, http://www.lookout.net/index.html would qualify as a URL, a URI, and an IRI. The 'scheme' part of this URI would be 'http', which refers to the specification that further defines how the URI parts should be processed.

The ABNF grammar for a URI scheme is defined by RFC3986 as:

scheme = ALPHA *( ALPHA / DIGIT / "+" / "-" / "." )

Quite simply, scheme names can only consist of the letters a-z, the numbers 0-9, and the three special characters '+', '-', and '.'. Uppercase letters A-Z in a scheme name would be canonicalized to lowercase as defined by the spec and as we see in most implementations. The syntax rules for a scheme are simple and do not impose arbitrary length limits, although most implementations will enforce their own length limit. Schemes are registered through an official IANA registry. Depending on who you ask, the process is not difficult but does involve some time and a manual review. The registry was designed to centrally coordinate and organize scheme registrations so they would be documented and publicly available. However over the years, many scheme names have been invented by application owners who did not use this process.

Protocol handlers in the Web browser

The DOM function navigator.registerProtocolHandler takes three parameters - a URI, a scheme name, and a title. These are used to register a protocol scheme name, such as http or mailto, to an arbitrary URI that should be used to handle that scheme. For example, you might want to let Hotmail register the 'mailto' protocol to be handled by some URI like https://www.hotmail.com/?email=%s The '%s' is required in the URI registration and will be replaced with the entire reference URI.

For example using the above registration, if you clicked on a link like mailto:chris@lookout.net the browser would open https://www.hotmail.com?email=mailto%3Achris%40lookout.net. In fact, the registration may persist at the OS layer, in which case it would be available to any application.

web+ is a new scheme prefix introduced by HTML5. I'm not clear on the purpose of this new prefix, but I can imagine seeing future schemes like web+tweet, web+like, and web+comment. In practice I suppose that application developers could register ad hoc schemes and would likely never go through the official IETF/IANA process. Some schemes would end up becoming popular and persisting while others would just fade away.

Risks to Security and Privacy

Many risks have been documented in the W3C specification including the following:

- Hijacking all Web usage

- Hijacking defaults

- Registration spamming

- Misleading titles

- Hostile handler metadata

- Leaking Intranet URLs

- Leaking secure URLs

- Leaking credentials

Others perhaps had not been considered or clearly listed, such as the capability to track users through unique identifiers appended to the web+ prefix, discussed more below.

Test results

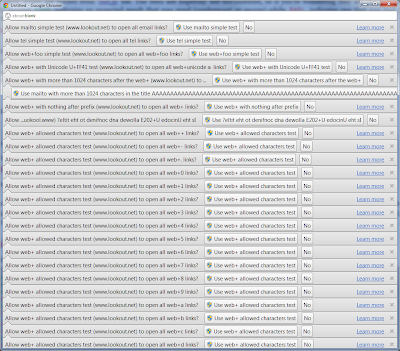

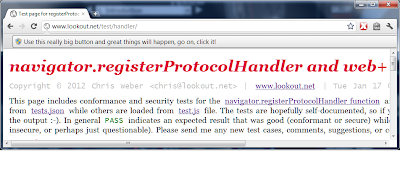

The table below can also be opened in a separate window summarizes the test results, which are discussed a bit more below. The test page is available online where you can quickly run the canned tests or create ad hoc tests.

As you can imagine, it would be devastating if one could register an arbitrary web+ scheme to the 'javascript' handler. As many XSS filters around the web intentionally block 'javascript:' in forums and comments, they would be immediately hosed when web+foo could achieve the same affect. It would be just as devastating if the 'http' handler could be controlled, so that all links ended up going to http://nottrusted.com?stealing=your%20data. Fortunately, all browsers tested prohibited such registration attempts.

Also fortunate, all of the browsers tested properly prohibited cross-origin registrations, even within the same general domain - registrations to a subdomain and parent domain were both prohibited, as were registrations to completely different domains. However, both Firefox and Opera allowed registrations to https from an http domain, but only Firefox allowed the reverse - registration from an https origin to http. Additionally, Firefox was the only browser to allow registrations to URIs with completely arbitrary ports, e.g. 23.

And what characters are allowed in a web+ scheme? The specification allows only the letters a-z after the prefix, but does not propose limits on length. Opera did not allow web+ registrations during testing, and both Chrome and Firefox allowed more than the small set of characters a-z. In fact, Firefox allowed any character whatsover to be registered, with or without the prefix, including any Unicode code point. Chrome only allowed the characters +, -, ., a-z, A-Z, and 0-9, in the ASCII range. Chrome was also liberal with Unicode and would allow most, but not all, code points above U+00FF. Of course this is pointless, because having anything but the URI-defined set of limited ASCII in the scheme would be prohibited and instead interpreted as a relative path in all modern Web browsers.

The User Interface seemed quite confusing in all cases except for Opera, which set the clearest message of the bunch. Both Chrome and Firefox used confusing messages that I cannot imagine a non-technical user would understand. Heck they were even confusing to me. Take a look at the following and judge for yourself, from top to bottom they are Opera, Firefox, and Chrome.

The primary spam protection is the infobar and requirement that a user must click 'yes' or 'no' to accept the registration or not. The UI could easily be flooded with infobars in Chrome, which tiled them vertically, making the Web page completely unusable after the window filled up, as in the image below.

One could also create a really long title, which would overflow the UI so the user would only see one big button, and would likely have little idea about what to do other than click the big button.

Firefox and Opera both at least overlapped the infobars so you would only ever see one at a time. Closing one would reveal the next one behind it.

It's also interesting to note how the registered protocol handlers would be stored. Chrome was the only browser that registered handlers at the OS-layer, making them available to all applications. In Windows this meant storing the registrations in the registry under the HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT hive, which required administrative elevation to register. In Ubuntu, they'd be stored in ~/.local/share/applications/mimeapps.list. Opera stored registered protocol handlers in C:\Users\chris\AppData\Roaming\Opera\Opera\handlers.ini where they were only available to Opera, and Firefox took the same approach, storing them in C:\Users\chris\AppData\Roaming\Mozilla\Firefox\Profiles\wj7x1dmj.default\mimeTypes.rdf where they were actually mapped using the URN protocol.

Here's what a 'mailto' scheme registration looks like stored in Opera's handler.ini file:

[mailto]

Type=Protocol

Handler

Webhandler=http://www.lookout.net/?mail=%s

Description=mailto scheme

Flags=16

And here's what some snippets of a 'foobar' scheme registration looks like stored in Firefox's mimeTypes.rdf file:

<RDF:li RDF:resource="urn:scheme:foobar"/>

<RDF:Description RDF:about="urn:handler:web:http://www.lookout.net/foobar=%s"

NC:prettyName="The foobar scheme"

NC:uriTemplate="http://www.lookout.net/foobar=%s" />

<RDF:Description RDF:about="urn:scheme:foobar"

NC:value="foobar">

<NC:handlerProp RDF:resource="urn:scheme:handler:foobar"/>

<RDF:Description RDF:about="urn:scheme:handler:foobar"

NC:alwaysAsk="true">

<NC:possibleApplication RDF:resource="urn:handler:web:http://www.lookout.net/foobar=%s"/>

Further testing

I tried clobbering some registration entries in Firefox using certain Unicode characters that would be best-fit mapped to ASCII. In other tests, some characters seem like they obviously should not be allowed in a scheme name, like control characters, for example, 0x09 and 0x01. However, tests at using these combined with some Shazzer vectors for characters allowed before the javascript scheme name did not work. While the registrations were allowed in Firefox, such as " javascript" with a leading SPACE, I believe some pre-processing removes that when encountered in an href attribute.

As far as penetration testing Web applications, we'll want to keep an eye out for usage of navigator.registerProtocolHandler, and closely inspect what the use case and implementation details might be. For example, it makes sense that GMail or Hotmail would want to register the mailto handler to their URL. Is that URL dynamically generated and can it be controlled by user-input? If an attacker could for example inject the hostname part of the URL then they could cause some mischief, or at the least steal email addresses and other data present in the mailto link. We'll also want to keep an eye out for registrations of web+foo schemes for similar issues including data ex-filtration and URL-control. I'm sure other folks can think of more threats and abuse cases, if so please let me know! Otherwise, time will tell.

Risks to user-tracking and fingerprinting

Another threat to consider is the way the web+ prefix would allow sites to set persistent unique identifiers in a user's Web browser. This issue was brought up by James Hawkins, author of Web Intents draft, on the WHATWG mailing list. It also became evident to me during testing when I realized I could set a unique identifier through the web+ protocol scheme - something like web+[some_unique_id]. Sites (from any origin) could later use the isProtocolHandlerRegistered(scheme, url) to identify its visitors, and even track their movement across the Web. As we've seen with trickery employed by advertising agencies in the past, those unique ids could be bundled and shared. However, the isProtocolHandlerRegistered API was not implemented during testing so I could not confirm this.